Tackling some of the common misconceptions above the atmosphere

A common misconception is that merely ascending straight up into space will result in a state of weightlessness or “floating.” This belief is often reinforced by media portrayals which can simplify or gloss over the intricacies of space mechanics. In reality, the sensation of weightlessness experienced by astronauts isn’t due to a lack of gravity in space. Even at the altitude of the International Space Station, gravity is about 90% as strong as it is on Earth’s surface. Astronauts appear weightless because they are in a continuous state of free fall around the Earth, perpetually “missing” it due to their high horizontal velocity. Simply shooting straight up without this sideways momentum would result in an object or person stalling and then being pulled right back to Earth. The sensation of “floating” in space isn’t about altitude; it’s about velocity and orbit.

- Escaping Earth’s Gravity: Technically, one never fully escapes Earth’s gravity as it extends indefinitely throughout space. However, its influence diminishes rapidly with distance. The “escape velocity” is the speed needed to break free from a celestial body’s gravitational influence without any propulsion. For Earth, this velocity is about 11.2 km/s. The further you move away from Earth, the weaker its gravitational pull becomes. Imagine you’re floating in space a short distance from Earth. If you were stationary, Earth’s gravity would pull you back. Now imagine you’re much farther away, say halfway to the Moon. Even if you stopped moving at this point, you would fall back towards Earth, but much slower than if you were closer. However, if you reached a certain distance where the gravitational pull of other celestial bodies is more influential than Earth’s, then you won’t fall back towards it.

- Weightlessness in Space: It’s a common misconception that there’s no gravity in space. In reality, a significant portion of outer space is under the influence of gravitational forces. Astronauts aboard the International Space Station (ISS) are often said to be in “zero gravity” or “microgravity,” but they are still affected by Earth’s gravity (about 90% of what we feel on the surface). The reason they appear weightless is that they, and the ISS, are in free fall towards Earth. Imagine being in an elevator and the cable suddenly snaps; both you and the elevator are in free fall, and you would feel weightless inside, even though gravity is very much at play. Similarly, astronauts and the ISS are falling towards Earth but moving forward fast enough that they continuously miss it. This creates the sensation of weightlessness.

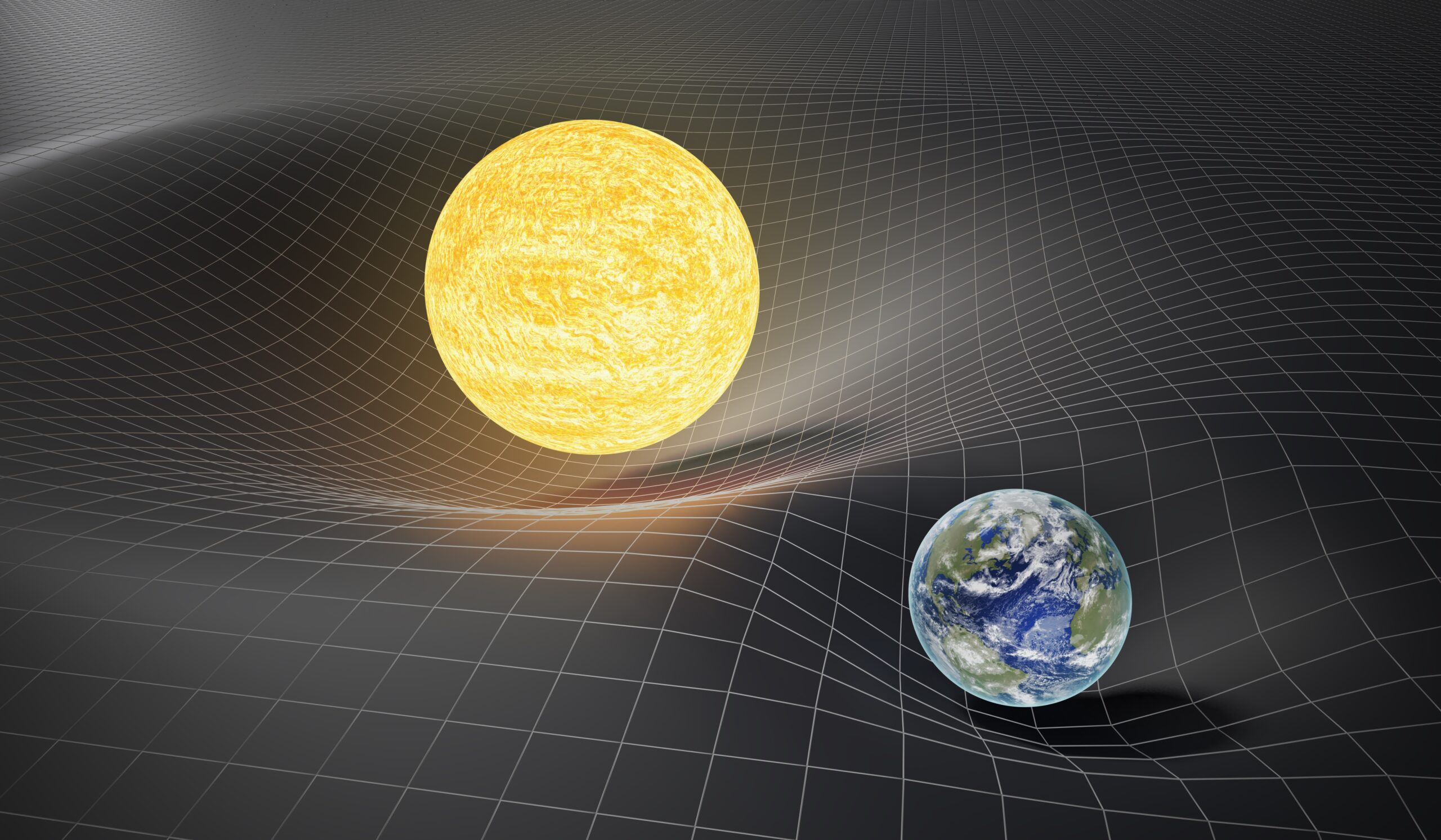

- Orbiting in Space: An orbit is essentially a balance between forward motion and gravitational pull. If you were to throw a stone horizontally on Earth, it would eventually fall to the ground due to gravity. If you could throw it hard enough and fast enough, though, it would fall around the Earth rather than into it. This is the basic principle of orbit. Spacecraft, like the ISS, move at such speeds that as they are pulled towards Earth by gravity, they keep missing it. They are perpetually in free fall around Earth. The faster the object moves, the higher and more elongated its orbit can become.

- Planets Not Colliding: The planets in our solar system, including Earth, are in stable orbits around the Sun. They’ve achieved a balance between their forward momentum (from when they formed) and the gravitational pull of the Sun. If planets only experienced the Sun’s pull without their own momentum, they would indeed crash into the Sun. But their initial momentum keeps them in orbit. Furthermore, the vast distances between planets ensure that their gravitational interactions with each other, while existent, aren’t strong enough to drastically alter these orbits. Over billions of years, many of these orbits have become stable and adjusted so that the likelihood of collisions is very low. Additionally, planets do exert gravitational forces on each other, leading to perturbations in their orbits, but these are generally minor and often balance out over long periods.